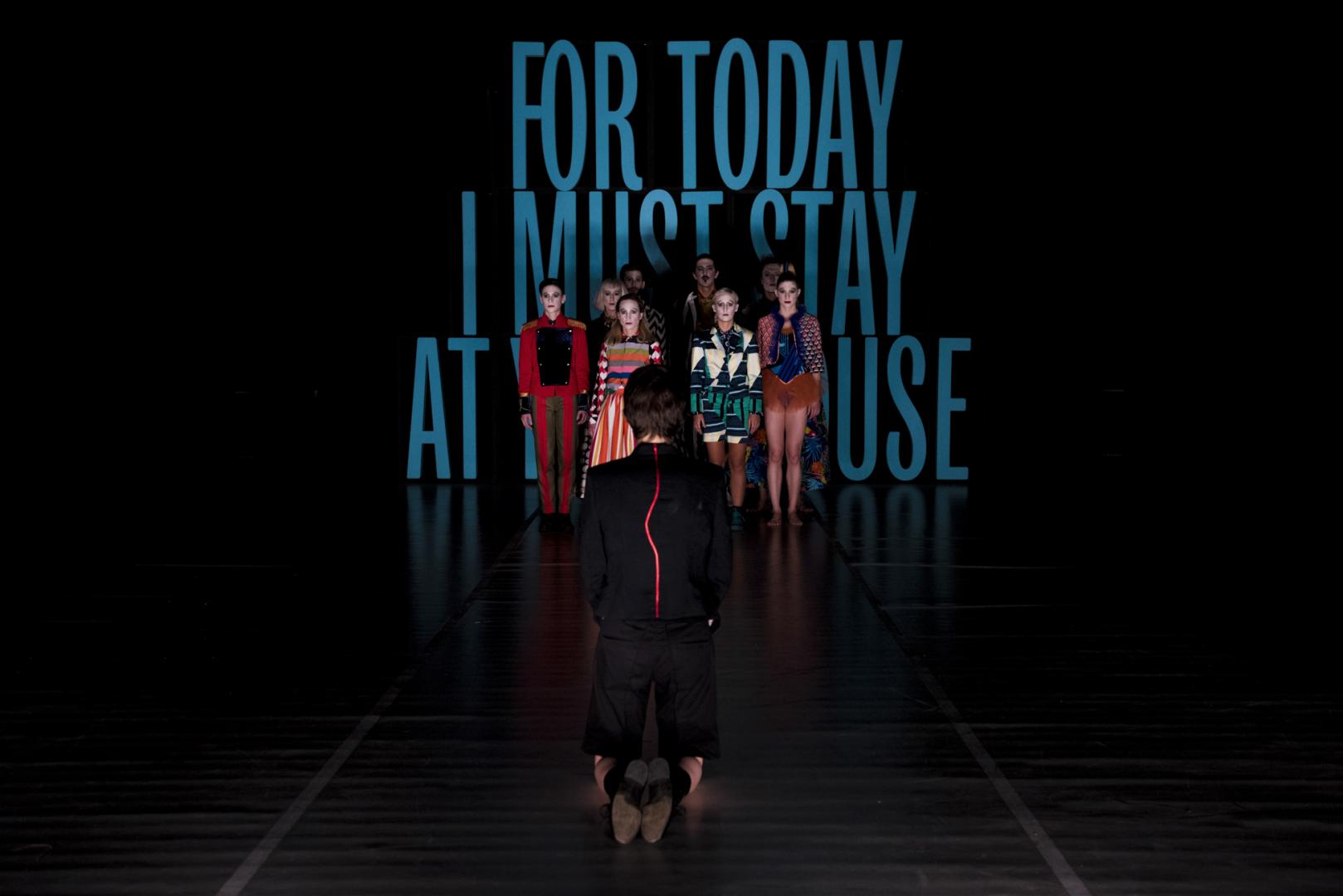

Staging a Play: Tartuffe

Opening night: 25.11.2017

About

After staging Tennessee Williams’ play The Glass Menagerie, which functioned as the basis for the creation of the first piece in his Staging a Play cycle, choreographer and director Matija Ferlin has chosen one of Molière’s classic comedies as the second play of his cycle. Although Ferlin has already authored several pieces which include certain forms of performative text (Samice, Istovremeno drugi, Mi smo kraljevi a ne ljudi, Sad Sam Lucky), this cycle represents the first time this author has tackled the canonic works of the dramatic arts.

Of course, in line with the specific poetics that Ferlin has developed while working on his other projects, the mode in which they are staged as part of the Staging a Play series questions the very foundations of the way the concept of staging a play is interpreted within the dramatic discourse. In this case, this involves the translation of a dramatic source text into the domain of choreography.

More specifically, verbal lines are replaced by a physical vocabulary, and the textual template is instead used as a complex choreographic score. This enables Ferlin to create a space of play on the stage, where the traditional modes of interpretation of Molière’s work, i.e. analyzing what is being said, are suspended, and where the narrative’s ownership of the performance is annulled. Instead, the body becomes a means of manifesting the concrete meanings that are written into each line, without trying to reach the same level or the same type of transfer of the content of communication.

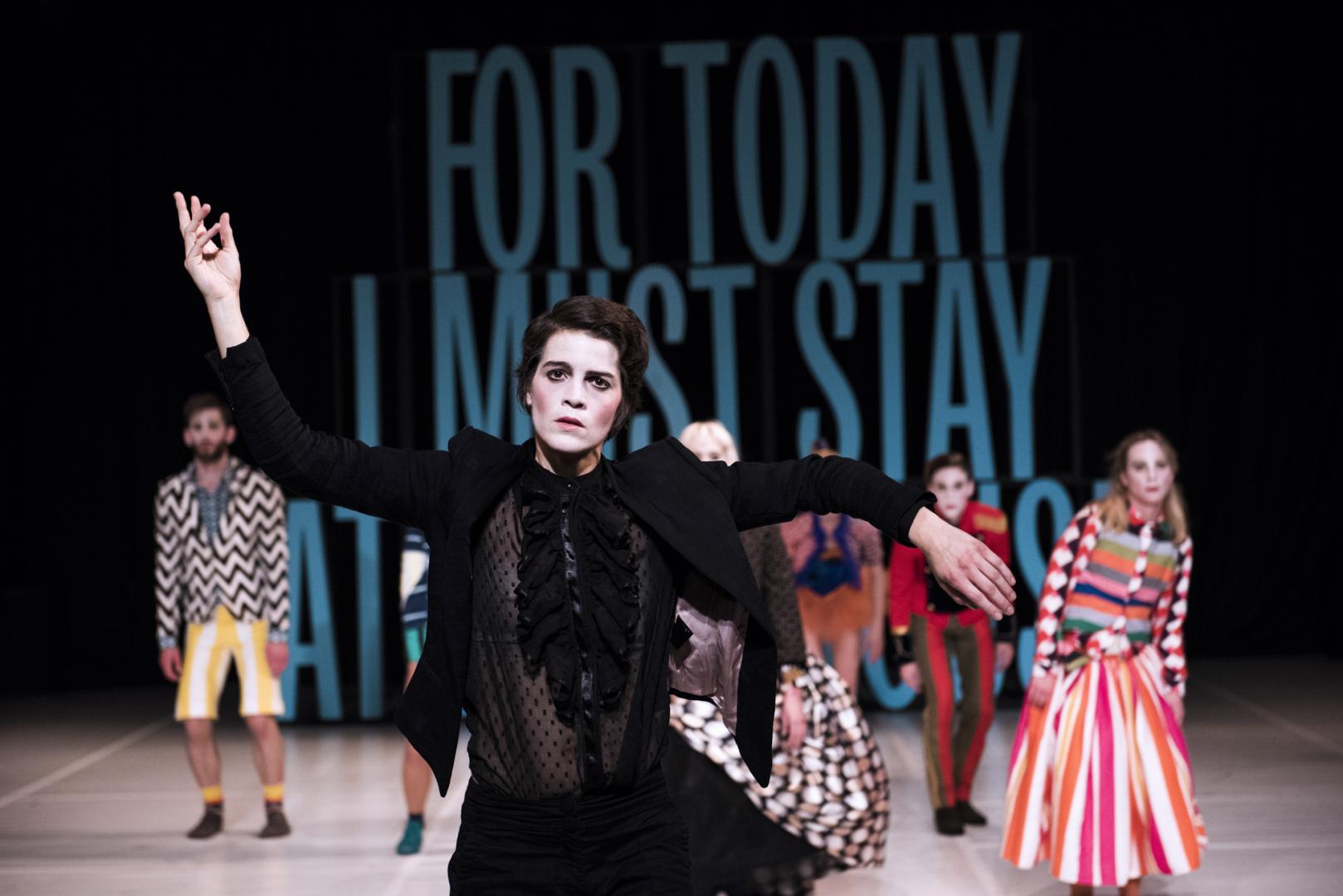

According to the explanation of the performance of Staging a Play: The Glass Menagerie, this means that: “the dramatic narrative written into the situations, statements and relationships of the dramatic characters transcends the boundaries of its synopsis as the vessel for dramatic dynamics and moves into an un-signified and abstract space where the code of speech is transposed into the code of choreography. The conflict moves from dramatic space into the space of the stage, into a broad field of negotiation between speech and movement.” In other words, bodily movement becomes not only the dominant, but the exclusive mode of communication.

Of course, this shifting of the performative material from the field of drama to the field of choreography serves to annul the potential for the exploitation of a specific interpretative layer inherent in verbal communication and dramatic theatre, which changes the very nature of our entire interpretative apparatus, reducing the domination of aural perception in favor of visual perception.

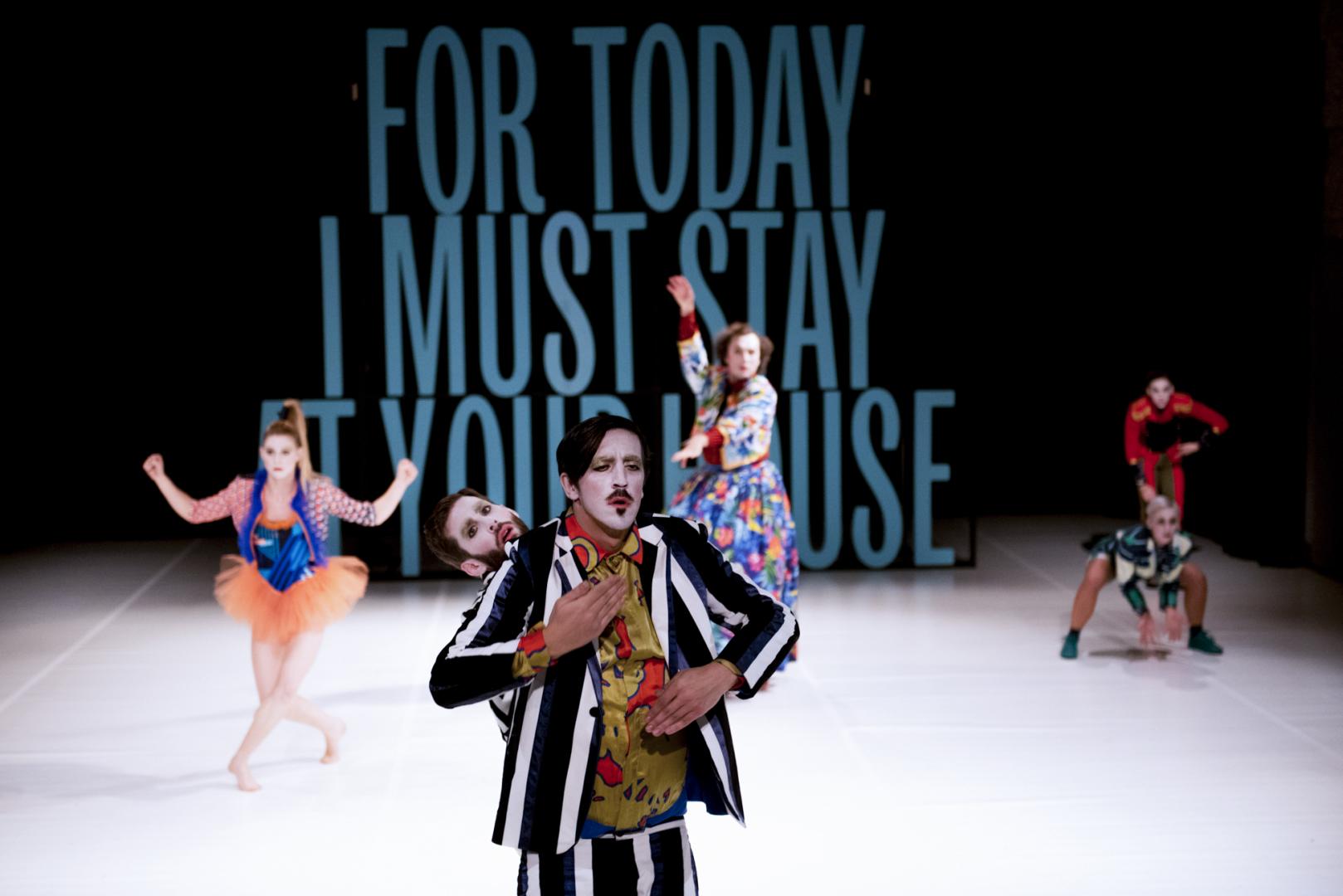

The characters are thus no longer reduced to their language and words, instead becoming their own bodies and movements, and their interrelationships are no longer mediated primarily through speech, taking place in the performative domain, while the tenacity of their gazes almost insists on establishing this new regime of perceiving. Even though this inversion is inevitably present in many artistic works, in the case of this project, the perspective of the dramatic source text lends this interpretation some new, interesting connotations.

For in the beginning was the word - but the word was transformed into movement, and the sentence, then, became dance.

Keeping together, for the entire duration. the performances of all nine characters, all nine performers dancing through the five acts, or thirty-seven scenes, Ferlin has created a complex performative apparatus in which bodies in space become the only vessel for the narrative, which over the course of the performance continuously shifts between attempts at deconstruction and attempts at reconstruction.

All the while, this bodily expression does not follow dramatic conventions, but rather arises from a conceptual treatment of movement, which vaccilates on the boundary between the illustrative and the abstract, repeatedly demonstrating the possibilities for expansion. By avoiding the literal nature of gesture, while constantly alluding to it, a subtle choreography of meaning is created, one whose registers were never rigidly fixed in place, and which is joined by a parallel orchestration through the presence of an entire dance ensemble which never leaves the stage.

Engaging a sophisticated choreographic mechanism, one that he has already developed over previous dance projects, Ferlin uses this project to occasionally collide it against concisely elaborated choreographies which, alongside the almost constructivist costumes, paints the source text in an unfamiliar light and thereby open up new possibilities of staging and interpreting it.